In a previous article I promised that I would share a measure of the improvement we are seeing in the clinical information on our request forms. As you may know, the Hywel Dda University Health Board is committed to seeing reductions in all aspects of healthcare associated infections and has set themselves the target of reducing E coli bacteraemias by 20% as a global surrogate of all infections across our area.

Why is clinical information important?

Microbiology does not provide explicit answers to the question, “Does this patient have an infection?” Our laboratories will grow bacteria but are bodies are home to 100,000,000,000,000 organisms other than the one we know best: ourselves! When we get an infection, it is the organisms we have acquired in that number that cause the infection. So whenever a lab grows or detects an organism, the clinician reviewing the result needs to answer a new question, “Does the clinical picture suggest the organisms the lab has grown are the cause of an infection?” This is not always straight forward.

We get requests for examination from many sources in the health service and while I expect the medical team to be aware of the questions above, others who may be submitting samples may not. This therefore remains a hugely important educational point.

Without the explicit clinical information, we cannot be sure we are going to help answer the clinical question by putting up the appropriate tests. Equally, as the final authorisers, our clinicians cannot be confident that person receiving the result will take the appropriate action. We know anecdotally that often one member of the busy healthcare team will say to the doctor, “Mrs Jones has a urinary tract infection, can you prescribe an antibiotic? I’ve taken a test and the organism is sensitive to amoxicillin.” We work in teams, we may assume that the information provided is correct and particularly in an older patient, may end up prescribing an antibiotic when instead of a UTI, they have bacteria living harmlessly in their bladder (“asymptomatic bacteruria”.)

What are we doing about this?

We use a number of standard comments, which we can tailor for specific circumstances. If I have a urine with no clinical information provided, I tend to use the comment:

“No clinical details provided, therefore no sensitivities reported. Please call the on-call consultant if antibiotics are indicated for clinical evidence of infection. Asymptomatic bacteruria in commonplace in older patients and antibiotics are not indicated and may select for increasingly resistant organisms.”

Similarly, with the anecdote I provided in an earlier article about a patient experience, where all we have in the clinical information are details of results of urinalysis (the urine dipstick test), I will normally advise:

“Dipstick results only given on the request form; no clinical information regarding signs or symptoms, which should always be the precursor to using a dipstick. Asymptomatic bacteruria is commonplace in older patients but also in younger people if there are underlying anomalies and antibiotics should be reserved for clinical signs of infection. Sensitivities therefore supressed. Please call the on-call microbiologist if antibiotics are clinically indicated.”

On the other hand, where there is clear clinical evidence of infection but a direct clinical question to the laboratory, I will seek to answer any questions being posed, this includes offering explanations around treatment failure, and at the very least reassuring the requester that the isolate is sensitive or resistant to the antibiotic the patient is receiving.

Around the start of the year, we decided that not releasing antibiotics is probably a useful tool in our efforts to support our antibiotic stewardship programme. Readers will have seen the headlines around antibiotic Armageddon and it is a real fact that we are seeing increases in antibiotic resistance locally. As a result, while we used to have similar comments to those above, we now are suppressing sensitivities more often and indicating to the clinicians that if there is true evidence of infection, to make contact with us to discuss what antibiotics are available.

What has happened?

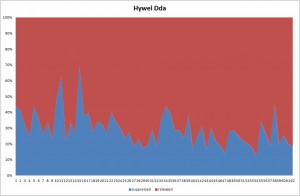

I have been keeping a simple tally whenever I am on authorising duties. Whenever we have sensitivities available, I have noted the number where I have released sensitivities and the number where I have suppressed sensitivities. The graph below shows what has happened over time.

This is a proportional graph. Each data point shows the proportion of results suppressed and released. Each is simply the sequential days when I have been authorising. This includes my weekend on, when numbers of new specimens are lower and to some extent explains why there can be quite high numbers suppressed on some days.

This is a proportional graph. Each data point shows the proportion of results suppressed and released. Each is simply the sequential days when I have been authorising. This includes my weekend on, when numbers of new specimens are lower and to some extent explains why there can be quite high numbers suppressed on some days.

Now it may be the “eye of faith” but I hope you will agree that as time progresses to the right, the number of times sensitivities are released is increasing. This is a reflection of the quality of the information appearing on the report and does indicate an improvement over time. The time frame here is only a matter of 6 months or so and does not compare to the longer data series presented in the previous article and graph, where I showed how the number of urines submitted was decreasing but primarily those that are ultimately negative.

The big question, of course, is whether we can yet see an effect on the E coli bacteraemia rates we are measuring in the acute hospitals. More analysis on that to follow.

Leave a Reply